System Mapping

The ecosystem map is a synthetic representation capturing all the key roles and dynamics that have an influence and interact with the environment of an entity (individual, team, organization). The ecosystem map usually entails and describes different entities, flows and relationships that characterize the surrounding ecosystem.

Process / Implementation

Systems mapping or modeling can be used as a sensemaking and communication tool when trying to understand the elements of a system, to bridge an idea from concept to action. It is a method for giving form to ideas - and structure to processes - that might not be articulated outside the mind or intuition. We can use modeling at any phase of a process to create visual displays that share projects and engage potential stakeholders. There are a number of different ways you might approach mapping the system to represent system elements and connections (find an explanation of how to do so here). For example, you might create:

Actor maps, to show which individuals and/or organizations are key players in the space and how they are connected

Mind maps, that highlight various trends in the external environment that influence the issue at hand

Issue maps, which lay out the political, social, or economic issues affecting a given geography or constituency (often used by advocacy groups)

Causal-loop diagrams, that focus on explicating the feedback loops (positive and negative) that lead to system behavior or functioning.

Different groups of stakeholders and dynamics you might want to include are:

Your core team: who is collaborating with you? Who is in the in-circle? What are their roles and responsibilities?

Your key partners: whom do you need to get your idea/project implemented? What is your relationships and how supportive are they of your endeavor?

People you don’t want to collaborate: who is soaking your energy? Who is opposing or even fighting or sabotaging you? Where do they block your actions?

Marginalized people or groups: Which are the voices not heard? What can you learn from them? What prevents them from coming to the center of the system? Where do their vulnerabilities lie?

Kelvy Bird from the Presencing Institute suggests the following process in modeling a system.

Source: eqstl.com

Part 1: What

To define parts is to seek sense and communicate arrangement within an existing wholeness. To name eg. tree, mushroom, frog, stream, pond, path, boulder is to identify elements of a terrain, guideposts for movement within a landscape. We distill to the bits to help objectify segments of what we see and thus locate within what we believe to be real. We break things into subsets to better grasp the way things hold together and also reveal how they might not.

A model is a snapshot in time, a cross-section of a perceived order, one picture of a moment: a past state, a present reality, an imagined future – each resting in unfolding life.

Models can incorporate change and reform over time. It is through the act of crafting a model that we can actually probe into our understanding of trajectories. If one day two parts align and the next day they repel, what is the underlying structure of relation causing this magnetic switch? A model can give voice to the dynamic.

Visual modeling serves at the structural level of the iceberg, to outwardly reveal the internal theories influencing behavior and events/actions.

Results vary. Parts move. Systems adapt in time. The foundational container holds steady. The model simply lays out components of this order, already existing, needing a hand to map it to life.

Part 2: How

Modeling is particularly useful as a sensemaking and communication tool when trying to understand the elements of a system, to bridge an idea from concept to action. It is a method for giving form to ideas – and structure to processes – that might not be articulated outside the mind or intuition. In the context of Theory U, modeling can be used at any phase to create visual displays that share projects and engage potential stakeholders.

EXPLORE and PRACTICE

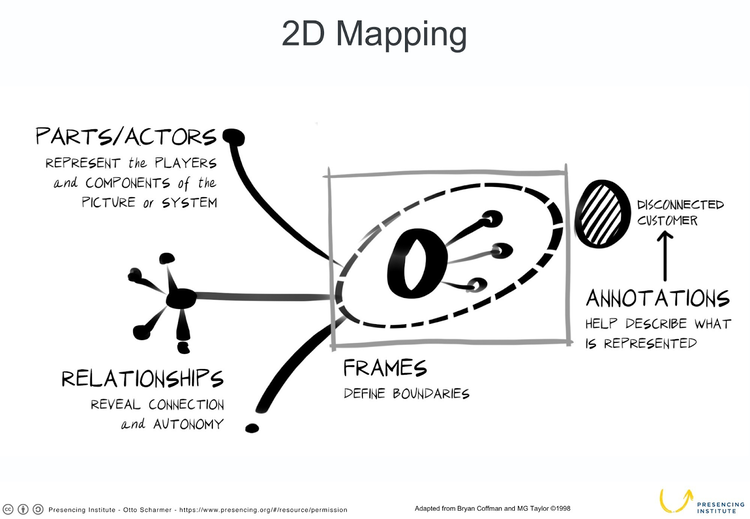

Level One: Parts (“Actors”). Actors represent the people and components of the picture or system. On a blank sheet of paper, practice drawing abstract shapes and textures of all sizes. Start with circles, ovals, squares, rectangles, triangles, etc, to get your hand familiar with the materials and to find your comfort zone with drawing. Also explore different textures, for example: dotted edges, solid lines, filled areas, speckles, swirls, etc.

Level Two: Frames. Frames define boundaries and can help sequence actions over time and place. Think of frames as an ordering device, like acts of a play that together tell a story. Draw different types of boundaries as frames, including boxes, larger circles, or even using the edge of the paper as the frame.

Level Three: Relationships. Relationships reveal proximity and interdependencies. Use arrows to show influence. Play with drawing shapes of similar and different sizes. See what they look like next to each other, on top of one another, far away from each other. You can think of the shapes as people from above, as if you are looking down with a bird’s eye view.

Level Four: Context. Context provides meaning and reason for the story to exist. Include the essence of what is wanting to be seen and heard through your model. If the drawing does not yet represent this perspective, and the story is still emerging, use annotation (words) to help describe what you are wanting to convey.

APPLY to PROTOTYPES

Use the following questions to guide your modeling process, to help organize and represent the current state of your prototype into a visual display.

Level One: Name the Parts

Who is already involved? Who would you want to include?

What other elements – such as organizations, sectors, or locations – do you want to represent in the picture?

Level Two: Explore Frames

Are there phases to the development of your prototype?

Are there boundaries to the prototype that are important to describe?

Level Three: Establish Relationships

Where are connections between the parts and frames?

Are there disconnects worth naming? What parts might be excluded, intentionally or not?

How do YOU relate to the prototype and what might be your learning edge in the project?

Level Four: Reveal the Eco-System

Does the picture include your original vision and intention?

How does this root in an “emerging future whole, where there is a shift in identity and self?”

Needed time and tools

Paper and pen

This exercise can be done individual or in a group

A minimum of 15’ is needed and can be extended to roughly 90’

Personal experience

Eco-system mapping can be used in many different settings. I find it most useful to apply it in a project context to gain more clarity of the actors, dynamics and intentions of your project. It also reveals leverage points and blockages in your project. A map indicates directions and also shows you where you shouldn’t go. Your map might also change according to where and how you move along over time and what seems most important in the given moment. It literally can be used as a map that helps you to maneuver your eco-system.

Sources and Further literature

Severin von Hünerbein is in charge of the design and facilitation of collaboratio helvetica’s Catalyst Lab, a learning and design process created to support the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Switzerland. He started his career in training and facilitation with euforia 2010. After graduating from the University of St. Gallen (HSG), he has been determined to bring social innovation to the business world through creating brave spaces that allow a diverse group of people who would usually not meet to find new forms of collaboration, dream together and to co-create innovative and sustainable solutions for systemic change.

He is decorated with a MA degree in International Affairs and with a mind full of jokes, joie-de-vivre, and patience.